The Public Power Project is a work of passion and collaboration for a better energy future. Over the past year we took to the road and were able to see communities fighting to hold their utilities accountable, municipal utilities working hard to keep supplying power to their rural towns, and activists who are pushing their local governments to break from extractive investor owned models and transition to municipalization (creating a publicly owned power utility). Let us take you across the Midwest to share insights in this new blog series "Knowledge Is Power: Energizing the Midwest" and accompanying report, Coming Together for Equitable Public Power.

Part 2: Energy Self Reliance In Iowa's Driftless

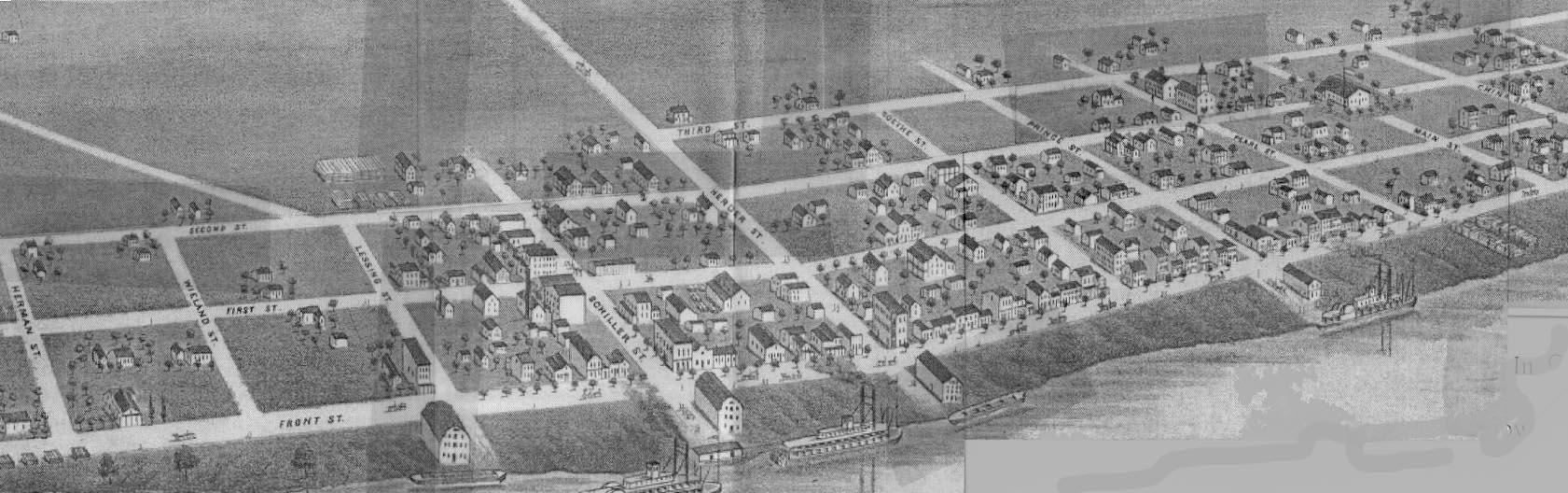

Nestled between the mighty Mississippi and soaring hills, a few rural Iowa towns are full of folks are taking power into their own hands. Our tour started in Clayton County, north of Dubuque.

The Driftless Region, as it is known, is a result of a continental glacier ice flow hundreds of thousands of years ago, which left rolling hills, underground water sources, caves, bluffs, and made way for the Mississippi and surrounding rivers and creeks. This beautiful region is an isolated oasis where communities often have to look inward to solve problems.

In this locale, residents have banded together to form county based “Energy Districts” to act as advisory centers for local co-ops, municipal utilities and community members.

Their goal? Strengthen their local communities by leading, implementing and accelerating an inclusive locally-owned clean energy transition - sharing resources and gathering information on ways to best meet energy needs in a rapidly shifting landscape.

Energy districts were created as a crisis response after the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent economic downturn. Local organizers realized the cost of energy was a widespread problem for residents that organizing and shared resources could help to ameliorate. The Energy District works closely with the three municipal utilities and several co-ops throughout the county with two purposes: connecting people with their best route to spending less money on energy and educating consumers of power on how best to move forward in the clean energy transition. We spoke with administrators and ratepayers of two municipal utilities in Guttenberg and McGregor to learn more.

GUTENBERG

Gutenberg is a picturesque river town of roughly 1,800 people. The town runs its own electric and water utility services, recently adopted net metering, and is in the early stages of developing a community solar project. Gutenberg gets power through group buying arrangements from larger power buyers that allow them to procure power at a reduced price. They then add charges which cover the city’s costs of distributing power, generate revenue for municipal operations, and act as financial buffer for rainy days.

From the staff of Gutenberg's utility, we learned that some of the smaller municipal utilities are dealing with an absence of highly skilled electricians wanting to move to rural power districts, especially when those districts may not be able to provide competitive wages. Furthermore, in the dilemmas to upgrading outdated systems, these decisions can be made quickly at the city level but ultimately come down to frank fiscal choices.

MCGREGOR

In McGregor, another river town with a population of just over 700 people that also does not generate the vast majority of their own power. The area tends to be a summer tourist destination with a corresponding economy. It’s also notable that the ease of communication with the community in a Municipal utility is a task to logistically consider well before forming a public utility. In a small rural community missteps in communication or clashing personas are more straightforward to fix but it is important your community feel engaged in energy decision making.

The energy burden in a McGreggor winter can be quite high, with most homes heated with propane. McGreggor, which is situated between large hills and the Mississippi, faces a unique problem. Its small size and location have made it so that there isn’t much open space for solar or prime real estate for wind generation. As such they purchase power through a co-op with buying agreements. This means they are reliant on a single transmission line to send power through to their lines. If something happens outside their system the city is at the mercy of the company that owns the transmission line to repair their connection to the grid or potentially fire up their petroleum burning generator, which they try to avoid. McGregor is sometimes called upon by the Midwest Independent System Operator (MISO) to turn on their generating unit when power supply is low, which has happened a few times in recent years.

MUSCATINE

The last Municipal utility that we visited was Muscatine, a city of 22,000 and east of Des Moines. We found that the structure of a municipal utility can help guard the utility against political influence and hold the municipal utility accountable, which is a level of uncertainty at the state level that many municipal utilities in IA are dealing with. However, Muscatine has been able to agree upon and build community solar, invest in EV charging in the city and reduce energy costs on public buildings.

The municipal power option works well for Muscatine in part because they are responsible for the city’s water, energy, and they are growing a communication utility. The revenue generated is put back into the projects they start and they are able to share resources across utilities. This is the benefit of their ratepayers being their owners - their primary interest is in lowering costs and building the community. They have been very effective in doing so for their ratepayers although there are some structural and accountability questions around whether the board should contain average ratepayers or only people with backgrounds in industry and finance.

In Muscatine, they have created a format to be studied as they invest in their community. In McGregor, their small and dedicated team is working to find solutions that meet their community’s needs. In Gutenberg, local organizers and public officials are working together to engage with their community and offer guidance and options to lower their ratepayers’ utility bills in a rural setting which often suffers from an absence of skilled electricians.

Each of these 3 municipal utilities are dealing with complex practical problems that are different but interrelated as our grid transitions in the effort to become a more sustainable society. It will be essential that these communities are considered and play a role in the transition to renewable energy. Especially because in many ways these self-starting communities are learning the knowledge of power generation that many communities have lost.

In Iowa’s Driftless, the conversation surrounding municipalization is rooted in a culture of self-reliance in a beautiful but sometimes isolated part of our country. Through building up their communities they have been able to protect and invest in their communities.

This is the second in a series of blogs exploring public power across the Midwest. Read other published blogs in the series and the accompanying report, Coming Together for Equitable Public Power.